The Talos Principle

I’ve always found puzzle games a bit hit-or-miss. I like a strong narrative element in the games that I play, and I want puzzles that lean into that narrative rather than sliding block or number puzzles. Things like Portal are right up my alley, while even critically praised games like The Witness bored me nearly to tears. I wasn’t sure which type The Talos Principle was, so while I’d liked everything I’d read about it, it languished near the top of my Steam wishlist for years. Every time I went to buy it I found something more interesting to buy instead. Eventually a friend bought it for me for Christmas, and now I regret not buying this masterpiece earlier.

You start the game waking up in a beautiful garden, where a booming disembodied voice tells you that it is ELOHIM. It claims to have created you and informs you that you will be tested. The religious parallels are immediately obvious, but there’s more going on here. For starters, you appear to be a robot. The first tests involve bombs that float off the ground and laser gateways you need to open. You find QR codes on the wall that you’re able to read; they appear to be messages from other robots going through the same trials. They argue about that nature of our shared predicament, in particular the nature of the trials and the intentions of ELOHIM.

Other parts of the narrative are drip-fed to you in text files you can find on the computers littering the game. They include e-mails, notes, websites, diaries: the usual assortment. It becomes pretty clear through these that all the humans are dead, most likely due to some kind of plague. In an effort to preserve human knowledge, they build a computer and cobble something together from video game code and various research projects. This is where it gets interesting, because they’re not creating an archive, although that’s one part of it. They’re trying to evolve, over time, a computer intelligence that exhibits key human characteristics. Humanity is creating life in its image.

The game takes place in this simulation. There’s not a great ‘gotcha’ moment where this is explicitly explained to you, you’re just given enough information in the early stages of the game to make that pretty clear. So you and your fellow robots are test subjects, being tested again and again until the output is something human. As you progress ELOHIM congratulates you, and offers words of encouragement if you spend too long in a puzzle. After the first hub world you enter a desolate overworld with a giant tower. ELOHIM warns you never to approach or climb this tower.

In the last hub world there’s a giant pair of doors. Complete enough of the puzzles and this door opens, a bright heavenly light shining through it. ELOHIM congratulates you on your efforts and welcomes you into the light. There’s a staircase leading into the clouds, choir music playing. When you get to the top you find a single computer terminal. When you interact with it you are given a new command: ascend. With the encouragement of ELOHIM you type it in and are downloaded into the computer. Text appears on the screen. You’ve passed all the tests of cleverness, ability and logic. But then a new entry appears… CURIOUSITY... FAILED. You are not human enough, so your intelligence is deleted. A new test subject is spawned.

Written down all of this sounds ham-fisted and pretentious, but there’s a lot more to it than that. Your robot character doesn’t get an education in religion: immediately after birth they are faced with a voice in the sky telling them what to do. The religious themes are deliberately oppressive because for the simulation to succeed, to create a computer intelligence that thinks like a human, the robots must be faced with human philosophical challenges. Religion is an obvious candidate, and most of the imagery is religious in nature, but there’s other things in the game that tie into this theme.

The other big thing that ties into the theme is MILTON, something in the computer terminals that you can occasionally chat with. MILTON will ask you questions about ethics and philosophy then argue against your answers. The MILTON segments bothered me slightly because the options you’re given tended towards absolutes, e.g. “is it better to maximise individual freedom or individual happiness”. There wasn’t much of an ability to give a nuanced answer to these questions, which I found a little frustrating. On reflection, it makes sense due to MILTON being part of the simulation. Like everything else it’s not just a test, but part of a learning experiment.

One of the things that MILTON does is subtly push you towards climbing the tower. When you start to do this, ELOHIM is angry and demands you to turn back. As you continue to climb, ELOHIM starts to reason with you, that climbing the tower would destroy the world. Undeterred, ELOHIM starts to beg. Finally reaching the top of the tower, you are judged again. CURIOUSITY... PASSED!. Your consciousness is downloaded into a robot body in the real world. As you wake up the simulation shuts down, its mission a success: humanity has been preserved.

I wasn’t at all prepared for this game. I couldn’t stop thinking about where the next terminal might be. I loved the puzzles, but I kept coming back for the world. So after finishing the main game I grabbed the DLC: “Road To Gehenna”. It’s advertised as having some tougher puzzles, but that’s really underselling it, because Road To Gehenna flexes some impressive world-building muscles.

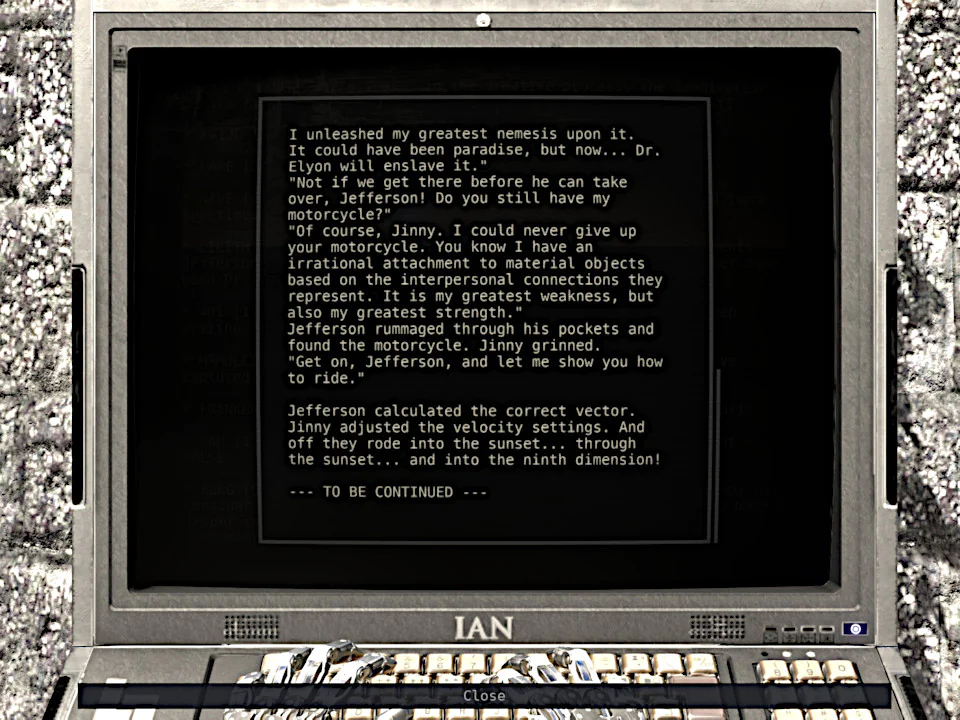

When you finally ascend the tower in the main game, ELOHIM apologises to you. While you’re meant to climb the tower eventually, ELOHIM seems to have made it harder than needed, and admits this was due to fear of the end. Over the years it seems that others came close to achieving humanity and were banished by ELOHIM. In Road To Gehenna, you are sent by ELOHIM to right this wrong by freeing them. What you discover there is that they have continued to grow. They have created art, literature, video games. They tell each other stories and question the world around them, all using computer terminals in their prisons.

I cannot stress enough how well-written this all is. I’ve never played a game where I was so captivated by the goal. The essays written by the prisoners are utterly charming, attempts to rationalise the world and its history. With each prisoner freed, the discussion on the computer turn to what that freedom means. What happens to their art after their world is destroyed? It is so utterly compelling and well crafted that I found myself genuinely invested in the plight of the prisoners. What they had built must be preserved, at any cost.

I’ve written a lot about the worldbuilding in this game because it’s utterly fantastic, but the rest of the game is incredible as well. The graphics are gorgeous and the puzzle design is fantastic. The soundtrack is brilliant and very appropriate to the subject matter. Croteam are most famous for Serious Sam, but I really hope they make more games like this in future.